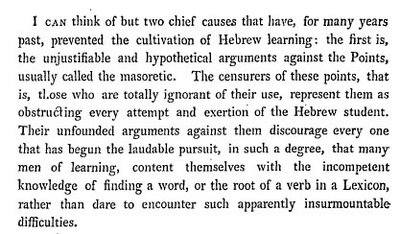

Not every reader of this blog already knows the history of typography, so I thought it might be worthwhile to discuss a curious fact that many readers must have noticed about printing in the 18th century.

Basically, what is the deal with the

fs (

effs) in place of

s?

The short answer is that it isn't an

f at all, but a "long

s." Happily, there is a good discussion of the issue on

Wikipedia. Short answer:

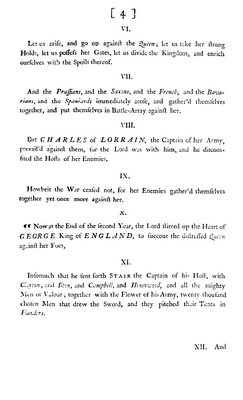

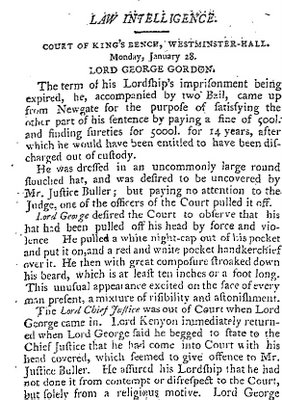

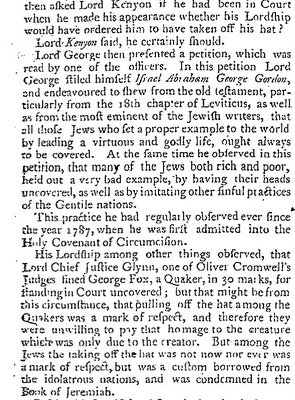

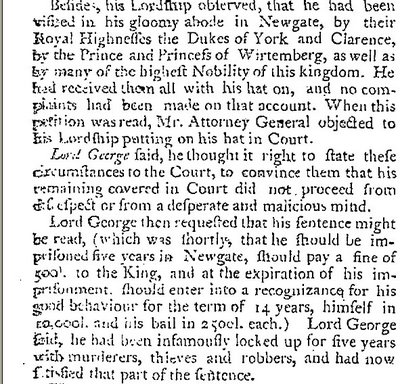

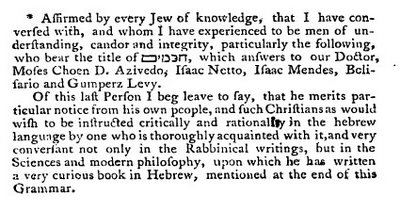

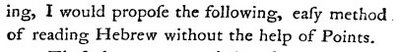

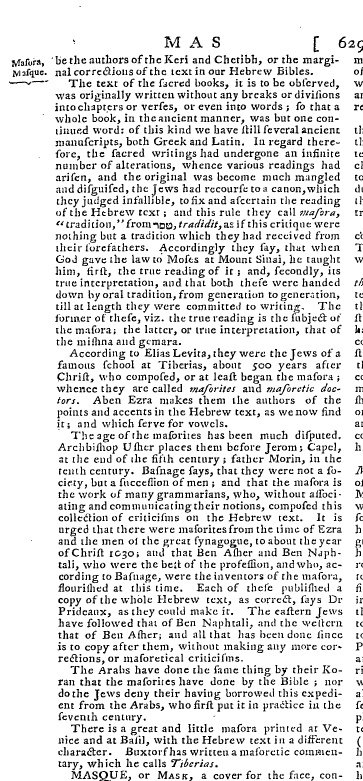

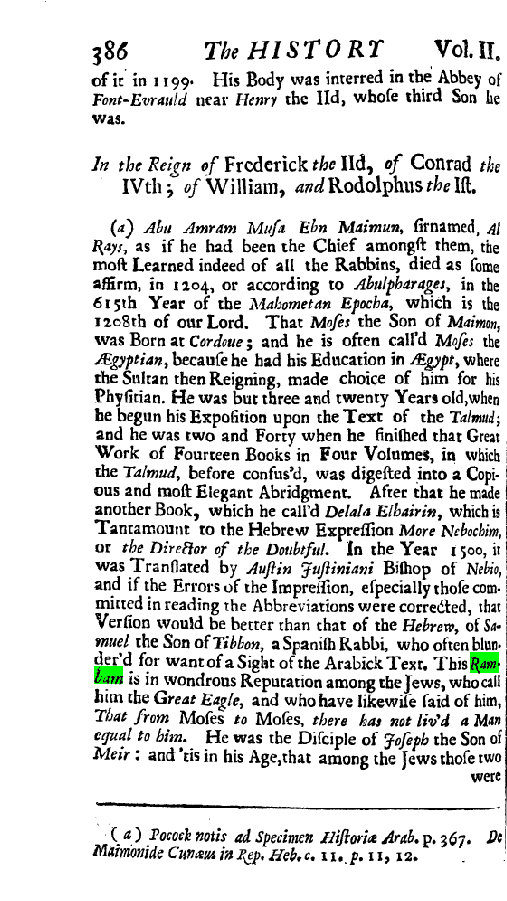

The long, medial or descending f (s) is a form of the minuscule letter s that was formerly used when the s occurred within or at the beginning of the word, for example finfulnefs ("sinfulness"). The modern letterform was called the terminal or short s.

Incidentally, the long

s was never identical with an

f in any of the fonts in use. It is just that in modern fonts the long

s doesn't exist, so here I am using an

f to represent it.

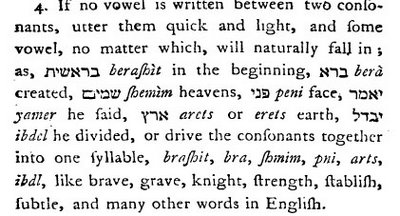

How was it used? The short answer is: never at the end of the words, always in the middle and sometimes at the beginning. Thus, you will find examples like this:

sufpicious and

fufcipious but never

fufpiciouf.

A question that might immediately spring to mind is, isn't that stupid? I mean, the letter form looks so much like an

f! The answer is basically, yes, it was a little silly and potentially confusin--and eventually the practice was stopped. But the truth is that many letters resemble one another. Take

u and

v or

h and

n or

q and

g (well, in some fonts anyway!) or

o and

0 or some forms of

i and

l and on it goes. Truth is, these are all easily confused (or confufed) with one another. Or take Hebrew, which is also full of letters that resemble each other. Examples:

ר/

ד,

ב/

כ,

ו/

ז,

ע/

צ ,

ג/

נ are all confusing for someone just learning Hebrew, no different than

ح/

خ are when learning Arabic.

So

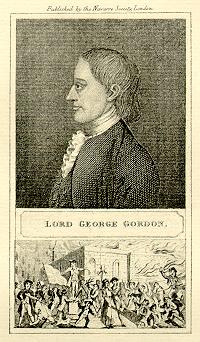

f/f is just another quirky example, long since corrected. In fact, one of the interesting things I think will be apparent in this blog is that one can see the evolution of the long

s from the beginning to the end of the 18th century. Pay attention to the dates of the examples I post and this will be apparent.